Israeli fish farmers are known for developing large, sustainable aquaculture systems that maintain livelihoods in many countries. Now a technique has emerged from Israel that is taking fish farms to a whole new level. Aquaponics is to fish farming what hydroponics is to vegetable farming.

Moti Cohen, developer of the first aquaponics farm, toolkit and consultancy in Israel, says the field has great potential.

Aquaponics most likely started in Asia, when a rice grower found that the rice in the paddies grew better when fish were swimming in them soon after the fields were flooded. The waste from the fish gave a nutrient boost to the rice. Similar effects were discovered by the Aztecs in Central America.

Cohen’s mission is to use today’s high-tech tools and knowledge of advanced methods in ecology to build better aquaponics systems beyond the hobby farm. He is creating systems that are easy to manage, control and give maximum yield.

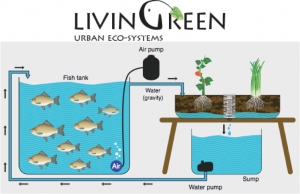

His company, LivinGreen Urban Ecosystems, builds, manages and in some cases maintains aquaponics farms.

Working as a special consultant to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Cohen has taught some of his techniques to farmers from neighboring states, including Jordan. Together with consultants from Ireland and Italy, he wrote the field guide on aquaponics for the FAO.

In 2014, LivinGreen led an educational project in Ghana, Africa, together with the Solar Garden. Systems were built using local materials and the teachers in the schools were given training courses.

Also in 2014, LivinGreen took part in an FAO project in which model hothouses were set up in several villages in Ethiopia. The university of Addis Ababa and local universities were involved in the project. Aquaponic systems were built in local agricultural schools, accompanied by training courses. Training workshops were also offered to delegates from various places in central Africa.

In China, in a collaborated venture between LivinGreen and the Chinese company AgriTech, this closed-system farm approach is being implemented commercially to raise fish such as Tilapia, catfish and carp together with tomatoes, Goji berries, lettuce and more.

The best of both worlds

Aquaponics has several advantages over traditional farming, aquaculture or hydroponics alone. It takes the best of all these worlds and puts them together.

Water for the fish can be obtained from brackish sources, and the ecosystem is easily purified over and over by the plants that live in the water-filled medium with the fish. It’s a kind of symbiosis: The plants feed off the ammonia and nitrogen in the water, while the fish enjoy the clean, oxygen-rich environment that the plants create.

“We have a biogas-integrated system for places where we can’t get fish,” says Cohen. “It’s a very flexible system. But it needs to be adjusted to the right place. Now we are fine-tuning a practical method to make aquaponics tools the best they can be.”

Cohen estimates that just a fraction of the water is needed to grow crops such as lettuce and tomatoes compared to land-based farming. Very little energy is needed, too. The system is powered by a small pump to circulate and monitor the water, and this can be fueled by biogas or solar panels.

And it’s not just about making great salads. At the end of the day, the goal is also to create tasty fish for food, an important source of protein for a resource-dwindling planet.

Natural fish populations worldwide have dropped, and nutrition and health experts are begging for new solutions not just in developing nations, but also in the West, where protein consumption is accelerating. Farmed fish using this method could be a good mercury-free alternative.

Researchers in Israel, including Dina Zilberg from Ben-Gurion University, are currently determining the optimal conditions for making farmed fish healthy and happy. She notes that farmed fish, however you grow them, appear to be “stressed” compared to the wild variety.

Farmed fish have bigger, fatty livers due to their diet and lack of natural movement. They are also prone to certain diseases when they live in captivity. Working on natural “cures” and ways to improve the conditions for fish on farms, Zilberg believes that aquaponics offers some improved ways for balancing and cleaning up the nutritious waste that the fish produce in captivity.

There is little research on fish health from aquaponics, she says, but “theoretically it is a really good idea because you take the water and use it for plants and this does some degree of cleaning before going back to the fish.”

The company is based in Hofit, just outside Michmoret on Israel’s Mediterranean shore, and has been in business since 2010. LivinGreen has built hundreds of aquaponics units in Israel and abroad, and has consulted for some of the world’s most prestigious organizations working toward improving the odds for people living at the base of the pyramid.

In the food pyramid, aquaponics seems to be able to offer a win-win situation, but Cohen cautions that it’s not a solution for everywhere, all of the time. It is good for urban environments like in Cairo, and it’s also good in places like Africa that are far from the sea where there is limited water availability and no regular access to protein. It’s also good for the West on rooftops and in backyards.

LivinGreen could answer some of the commercial needs of a planet in transition.